Most of the research into and the writing of the Fourth Story was undertaken during the latter part of 2018 through to the middle of 2021. The Covid pandemic disrupted progress and it was not possible to access some relevant source material until 2022 - some still remains unavailable. While finalisation of the narrative was frustrated in 2021 I commenced researching and writing up the Fifth (and final) Story, which I have now concluded and hope to publish before the end of 2022.

SD Oct. 2022

The Fourth Story

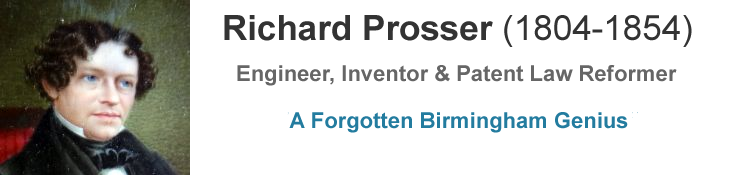

The Fourth Story examines the role played by Richard in the latter part of a campaign that had, in fact, commenced before the grant of his first patent in 1831, when he was a young engineer working in Birmingham’s cut nail industry. The, often thwarted, efforts of the campaigners eventually culminated in the enactment of legislation in 1852 which was to dismantle a Byzantine bureaucratic system of sinecures created in England over centuries to administer the grant of patents for inventions.

In 2012, when we knew virtually nothing about Richard, we were told on a visit to the British Library that Richard was an “unsung hero” for his contributions to the campaign and to the founding collection of the then new Patent Office Library. Our informant was Beryl Leigh, a retired librarian who for over 30 years had worked in the Library (part of the British Library since 1972).

The Story commences with an examination of what support exists for Beryl Leigh’s remark from historians, contemporary commentators and others whose careers, like Beryl’s, had given them significant insight into the subject of patent law reform in the 19th century.

Of the very many others who have received some recognition for their contributions to the reform campaign, four names stand out - those of: the now little known Bennett Woodcroft, who was to become the effectual head of the new Patent Office; the now virtually unknown Thomas Webster, a leading patent law lawyer; the still famous civil servant Henry Cole, later knighted by Queen Victoria; and the eminent lawyer, politician and statesman Lord Henry Brougham. Of these four, Richard was well known to the first three; Brougham, whose long and influential commitment to patent law reform was publicly acknowledged by Richard, had interrogated Richard when a witness before the Privy Council in 1843 at the hearing of the application to renew Wright’s encaustic tile patent (The Dust-Pressed Process pp.213/214). Brougham must have been aware of Richard’s outspoken support for the cause in 1850 and 1851.

Having briefly summarised the history of its development and the most significant of the many defects of the pre-reform patent system, what is known of Richard’s own knowledge of patents and patent law is reviewed.

Before embarking on a chronology of the reignited campaign in 1850, 1851 and 1852 (in which the Society of Arts played a much publicised part - thanks largely to Cole), two unrelated events in Richard’s life at this time are described.

The first relates to a subject touched on in the Third Story. Richard’s outspoken support of Lady Bentham, the redoubtable widow of the engineer and naval architect Brigadier General Sir Samuel Bentham, in her personal campaign for the recognition of her late husband as the inventor of the wood working machinery which revolutionised shipbuilding in the Royal Navy’s dockyards. Richard was to publicly denounce the late Sir Marc Isambard Brunel, Bentham’s protégé, for taking all the credit for his benefactor’s innovations.

The second event relates to Richard’s participation in the vociferous public debate on the dispute between the railway engineer Robert Stephenson, son of George, and the engineer and shipbuilder William Fairbairn as to which of them invented the tubular bridge; the first example of which was the Britannia Bridge, a railway bridge over the Menai Straits linking Anglesey to the mainland of Wales.

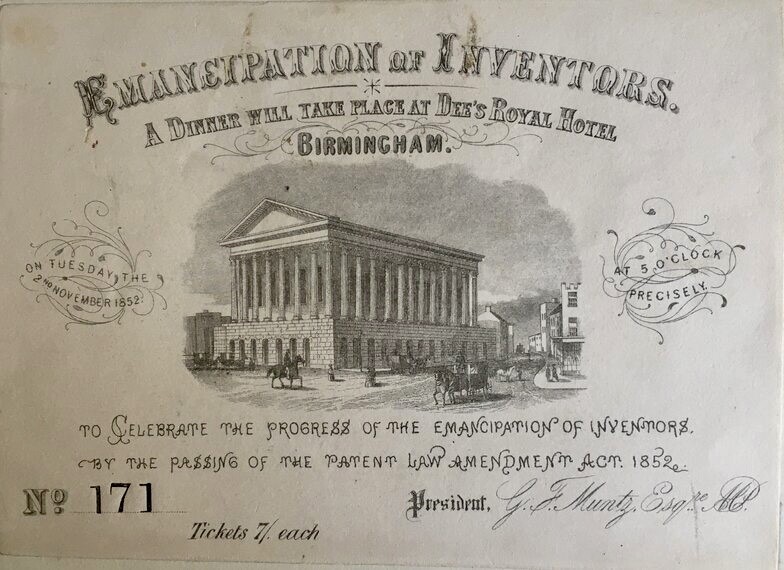

Richard’s proactive and constructive contributions to patent reform both before and after the enactment of the Patent Law Amendment Act 1852 are described. The Act only just scraped through the legislatures in the face of fierce opposition and filibustering from those politicians who opposed patents as a matter of principle. In celebration of its enactment Richard organised the “Emancipation of Inventors” dinner held in the Dee’s Royal Hotel in Birmingham; it was reported on at length locally, in The Illustrated London News, the London Daily News and in at least one foreign publication - the Scientific American.

The Story continues with a discussion of circumstances and events in 1853, including an examination of the backgrounds to the creation of the then much acclaimed library of the new Patent Office and of the nation’s still famed Science Museum. Richard’s contributions to the former and his advocacy for a national museum of scientific discoveries are examined. The Story ends with an account of a lively debate on patents that took place at the Society of Arts at the beginning of 1854, in which Richard was a prominent participant.

The Emancipation of Inventors - Download a PDF version

Image - Ticket for the Emancipation of Inventors dinner (Darby Collection).